What’s Wrong With China’s Economy?

What’s Wrong With China’s Economy?(Yicai) Sept. 30 -- Sentiment has soured on China’s macroeconomic prospects since the release of the second quarter’s .

Growth in the first half of the year, at 5 percent, was in line with the government’s full-year target. But analysts are concerned that the outturn for the second quarter was only 4.7 percent, 0.6 percentage points slower than in Q1.

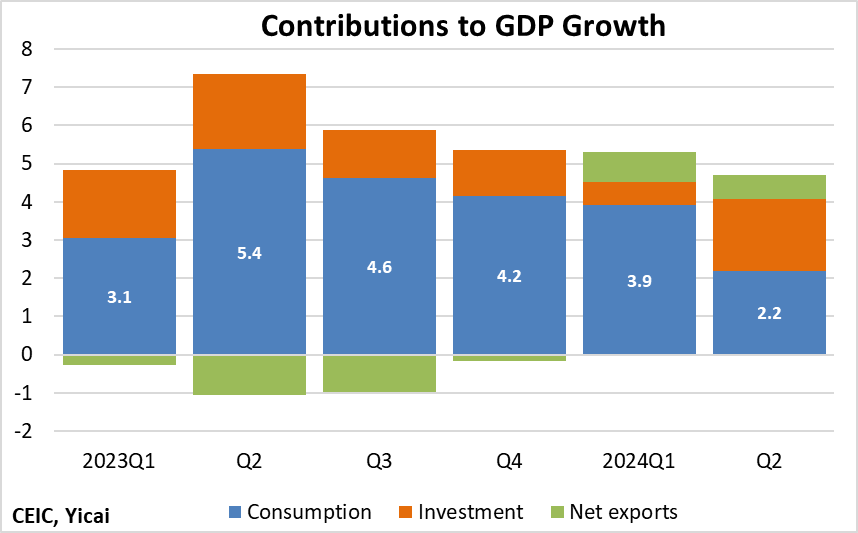

Much of the weakness in the second quarter came from consumption, which only contributed 2.2 percentage points to the headline 4.7 percent number (Figure 1). This was less than half the contribution consumption made over the previous four quarters. In contrast, investment’s contribution jumped to 1.9 percentage points while that of net exports remained positive.

Figure 1

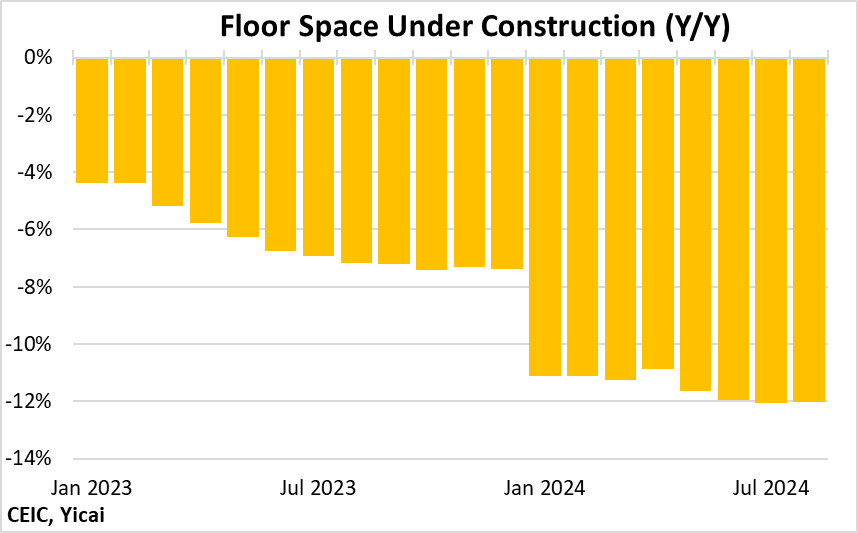

The property market correction is the source of much of the economy’s weakness. Construction activity has been dropping at an accelerating rate. Many projects have been completed in the last year, but few new ones have been undertaken. As a result, floor space under construction has been falling by 12 percent, year-over-year, in recent months. This is a much sharper decline than the 7 percent fall in the same period last year (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The property market is deeply intertwined with other sectors of the economy. It has upstream linkages to building supplies and downstream connections to household appliances and home furnishings. Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang use China’s input-output tables to estimate a comprehensive picture of the real estate sector’s importance. They find that, considering all the relevant linkages, residential and commercial real estate account for .

Using Rogoff and Yang’s estimate and floor space under construction as my measure of real estate activity, I calculate that the property market’s weakness is removing the equivalent of 2.3 percentage points from headline GDP growth. This is 0.9 percentage points more than it subtracted last year.

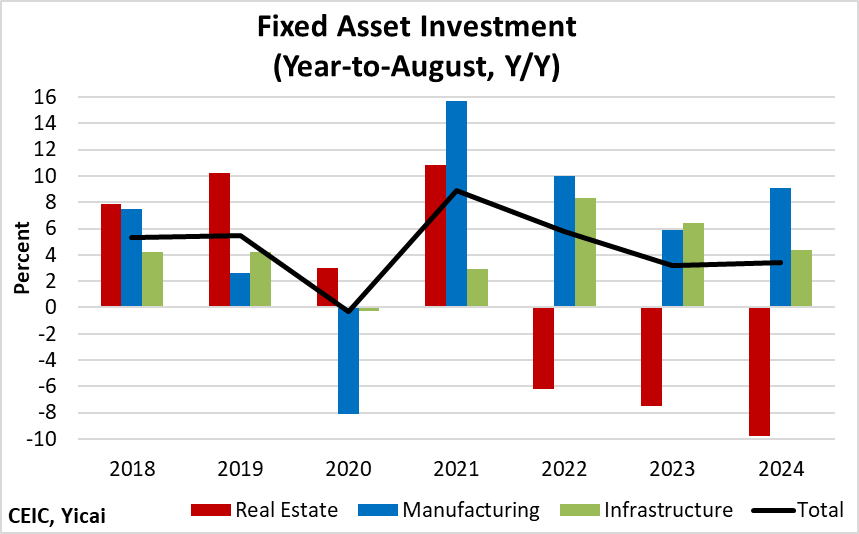

The weak demand for properties is evident in the fall of real estate fixed asset investment, which is declining for the third consecutive year. Moreover, the investment decline has been accelerating (Figure 3). Still, the other key investment sectors – infrastructure and, especially, manufacturing have been robust and have been growing more rapidly than before the pandemic.

Figure 3

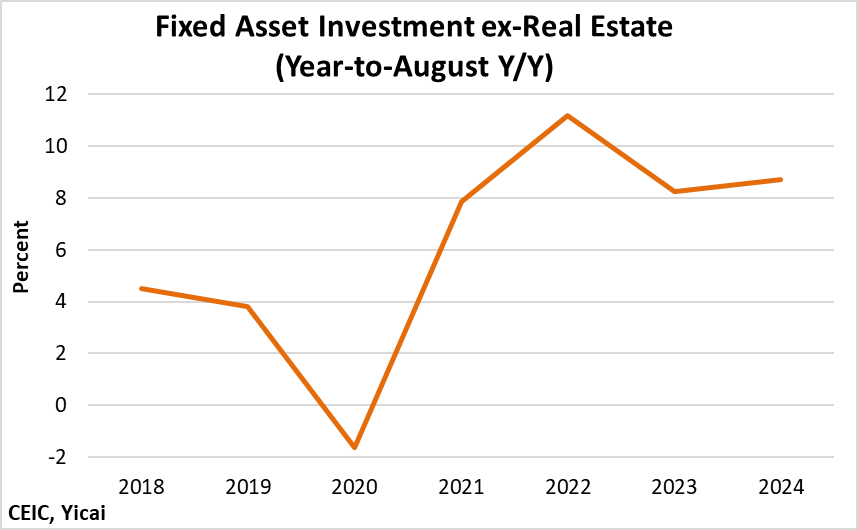

We can strip out the effect of the property investment decline from overall fixed asset investment. Doing so, we find that the growth of fixed asset investment ex-real estate, so far this year, is close to 9 percent or more than twice as fast as in 2018-19 (Figure 4).

Figure 4

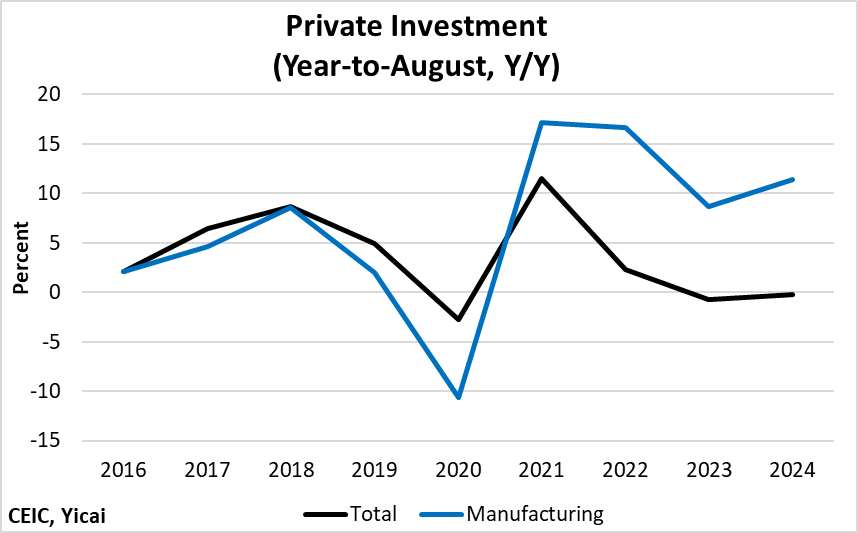

A similar story emerges when we focus on private sector investment.

Private sector investment has been stagnant for the last two years (Figure 5). However, real estate accounts for some of private investment. And real estate investment undertaken by the private sector is falling even faster than that of the state-owned enterprises. Looking through the gloomy headline number, there is reason for optimism. For example, private sector investment in manufacturing is doing very well thank you, with rates of growth well above those recorded in 2016-19.

Figure 5

Consumption is also feeling the sting of the property market downturn.

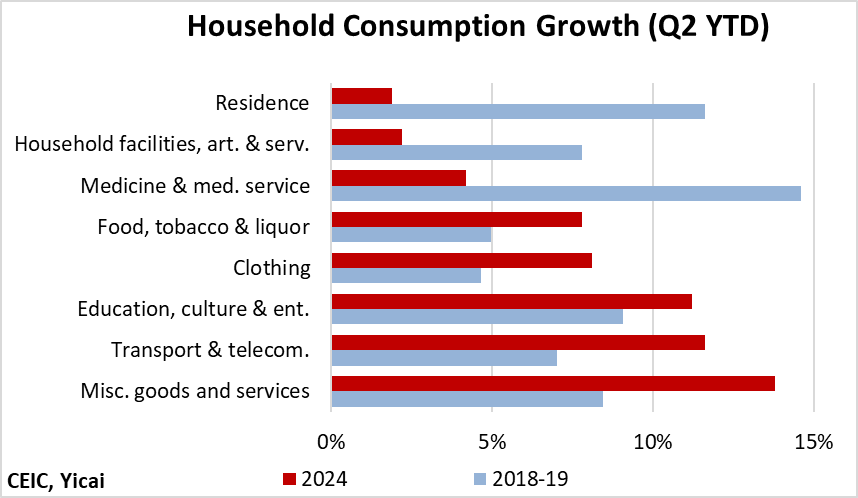

Using data from the National Bureau of Statistics’ , we can compare consumer spending growth in the first half of this year to the first halves of 2018 and 2019, on average. Consistent with poor home sales, spending on Residence and Household facilities stand out as being particularly weak areas of spending (Figure 6). Consumption growth in most other areas has been much faster than pre-pandemic rates.

Figure 6

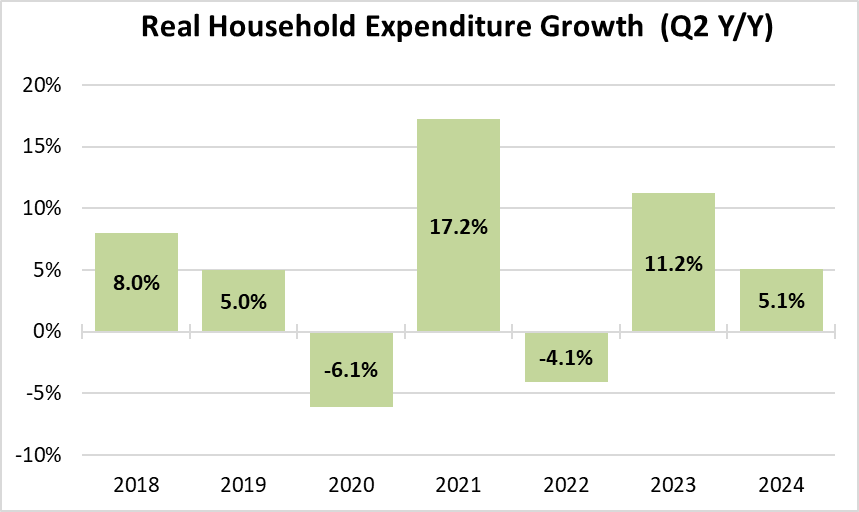

I estimate that household consumption growth in Q2 was just over 5 percent in real terms (Figure 7). This is somewhat weaker than the 6.5 percent recorded in the second quarters of 2018 and 2019, on average.

Figure 7

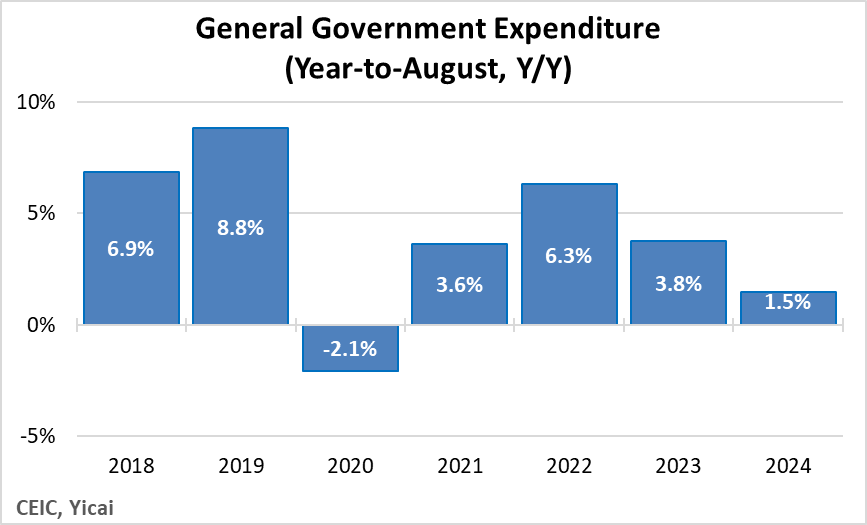

The National Accounts data combine the consumption of both households (70 percent of the total) and governments (30 percent). It is notable that general government expenditure has only grown by 1.5 percent so far this year. This is much more slowly than the 8 percent recorded, on average, over 2018-19 (Figure 8).

Figure 8

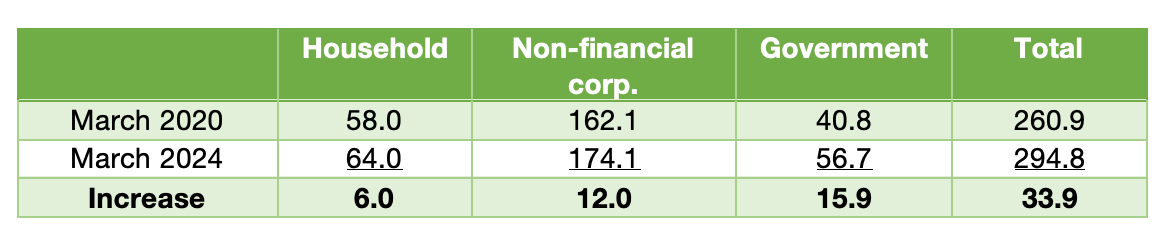

Governments are spending less for two reasons. First, revenues are down almost 3 percent so far this year. Second, governments are trying to de-lever. Over the last four years, governments borrowed heavily as they tried to offset the effect of the pandemic on the macroeconomy and public health. The increase in the government leverage rate was almost 16 percent of GDP. This was a bigger increase than that of households and non-financial corporations and accounted for an outsized share of the overall increase in indebtedness.

Table 1

Sectoral Leverage Ratios

(Percentage of GDP)

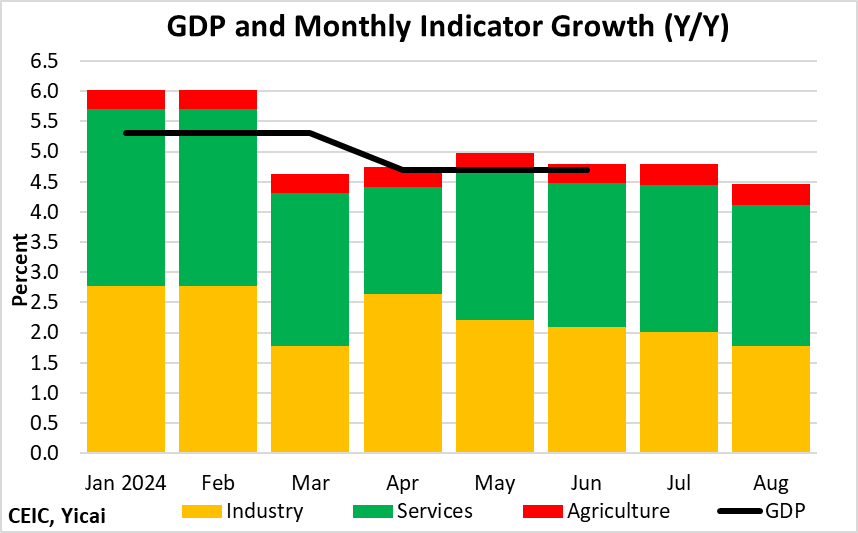

Unfortunately, the macroeconomic news appears to be getting worse. Our monthly GDP model suggests that growth over July-August may have continued to decelerate as industrial production growth slowed (Figure 9).

Figure 9

The authorities are concerned about the risk that they may not achieve their 5 percent GDP target this year. As a result, they recently announced a series of that lowered interest rates and made it easier for households to buy investment properties. The central bank is also providing financing for state-owned companies to buy unsold homes and turn them into affordable housing units and it has created tools to encourage the buying of equities.

These measures were in line with the pro-growth issued by the Politburo that, among other things, called for easing monetary conditions, stabilizing the property market, boosting the capital market and increasing the consumption of low- and middle-income groups. The Politburo also called for facilitating the investment of foreign capital in manufacturing and further improvements in the business environment.

Shanghai’s A Share market rallied significantly, indicating that the measures have catalyzed investor confidence.

My analysis suggests that China’s recent economic weakness stems from a property market that continues to deteriorate and government deleveraging. The recently announced measures will help address these problems.

Should the authorities need to go further, I have two suggestions.

First, homebuyers remain wary of committing what is typically 100 percent of the value of their to-be-built home to developers whose creditworthiness they cannot assess. Perhaps deposit insurance is a useful model here. I believe some sort of home-payment insurance scheme could be developed with the premiums paid by homebuilders. This would go a long way to underpinning homebuyer confidence.

Second, local governments are rightly addressing their indebtedness. However, reining in expenditures to reduce leverage can be self-defeating as it dampens economic activity. Fortunately, many of these governments have assets, including significant non-core assets. Selling these assets and paying down debt improves creditworthiness while maintaining growth. Certain governments are doing this. But some government officials are concerned about the reputational effects of “selling the crown jewels.” Thus, it would be useful to develop transparent frameworks under which government assets can be sold without compromising officials’ reputations.