Is China’s Trillion Dollar Trade Surplus A Sign of Weakness?

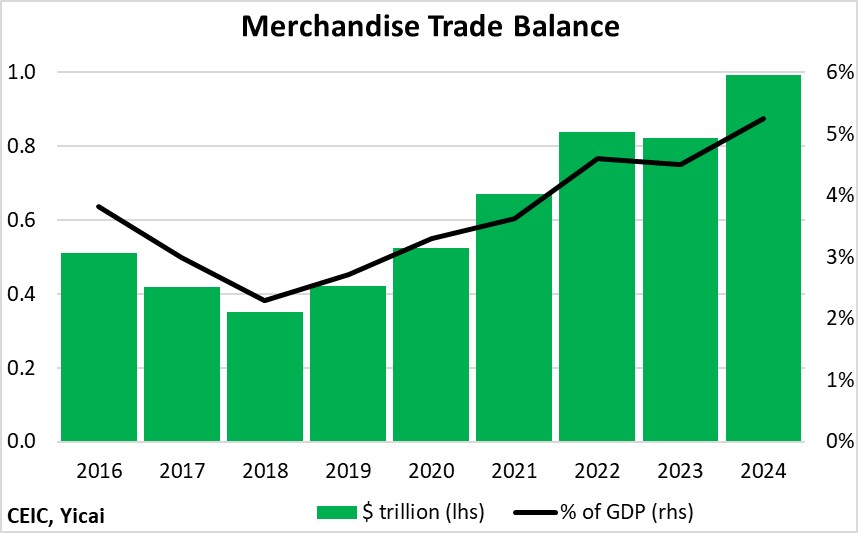

Is China’s Trillion Dollar Trade Surplus A Sign of Weakness?(Yicai) Feb. 21 -- China’s merchandise trade surplus neared $1 trillion last year, rising from $830 billion in 2022-23. This surplus accounted for over 5% of GDP—roughly double its share in 2019 (Figure 1).

The trillion dollar figure has attracted significant attention. For example, Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman called the surplus “a sign of weakness”, saying that it was a symptom of China’s inability to grapple with its fundamental problems.

Like all economic data, I think China’s trade surplus is best understood in a broader context.

Figure 1

For starters, a trillion dollars is a large sum but the US ran a merchandise trade deficit of $1.2 trillion last year. This was equal to China’s trade surplus plus the $200 billion surplus run by the Euro Zone countries.

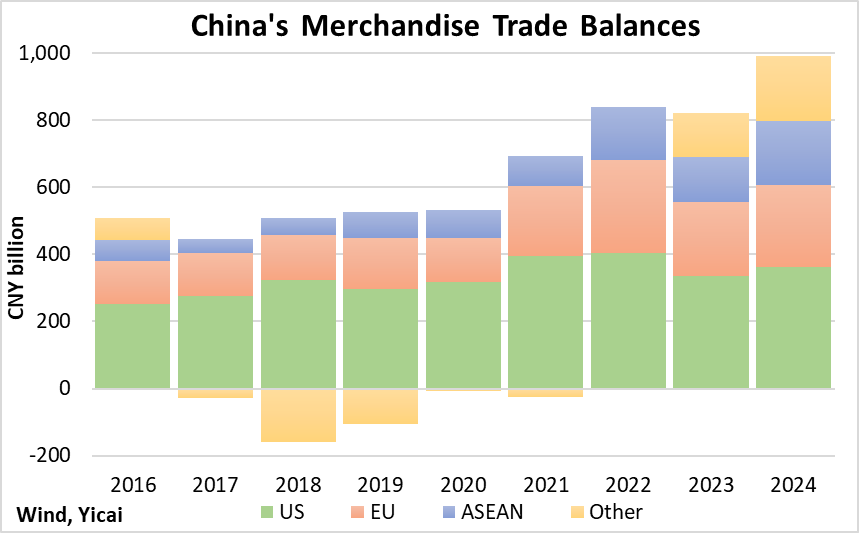

Of course, China did not run a trillion dollar surplus with the US. Its bilateral surplus was $361 billion, down from a peak of $404 billion in 2022 (Figure 2). Similarly, its bilateral surplus with the European Union was $247 billion, down from a peak of $277 billion in 2022. Over time, the increase in China’s trade surplus comes from a more positive balance with the ASEAN countries and a marked turnaround in its position with all other countries.

Figure 2

Some observers suggest that China’s large trade surplus must be the result of unfair practices like subsidies. Fortunately, recent work by economists at the IMF helps clarify this question.

By comparing products that are subsidized with those that are not, the economists were able to estimate the amount by which China’s subsidies affect its international trade. They found statistically significant evidence that subsidies both increase the exports and reduce the imports of a given good. However, the impact of the subsidies is relatively small with the level of exports increasing by 0.9 percent and the level of imports falling by a similar amount.

To estimate the maximum effect subsidies might have had on last year’s trade balance, we can do a simple thought experiment. China’s goods exports totalled $3.6 trillion last year and the value of its imports was $2.6 trillion. Let’s assume that all Chinese products are subsidized (this is not the case in reality). To estimate the effect of subsidies, we reduce exports by 0.9 percent and raise imports by 0.9 percent. Our estimate of the trade balance in the absence of subsidies is $937 billion just $55 billion less than the actual $992 billion surplus. This thought experiment suggests that – at a maximum – subsidies can only explain a very small amount of China’s trade surplus.

The Fund’s economists also critically assess the contention that China is exporting its overcapacity. Professor Krugman, among others, believes that China is compensating for weak domestic demand by running large trade surpluses.

The economists state that a “necessary although not sufficient condition for subsidies to aggravate a problem of excess supply in global markets is that they lower export prices and increase export quantities.” They are careful to note that factors other than subsidies, for example efficiency gains, can also lead to lower export prices and higher export quantities.

Nevertheless, across all goods, the researchers are unable to find statistically significant evidence that the subsidies lead to lower export prices and higher export quantities and that China is exporting its overcapacity.

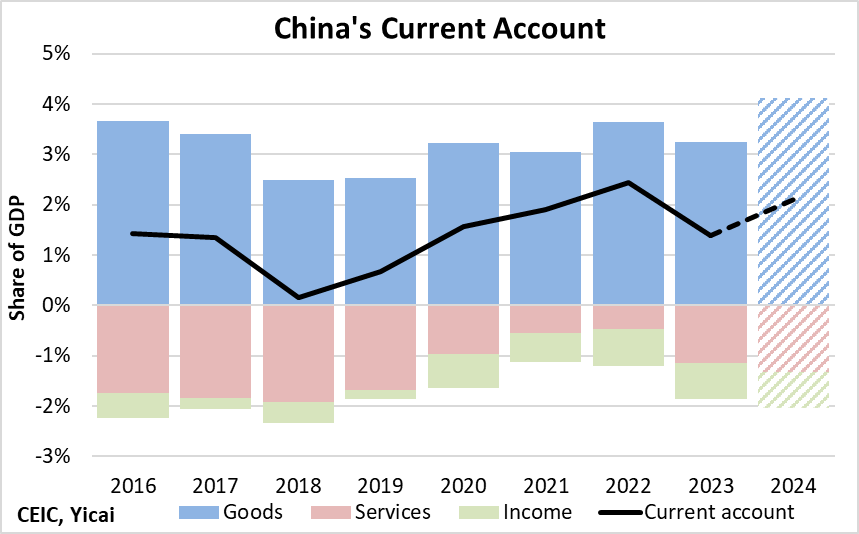

Merchandise trade is only a part of China’s overall balance of payments. While China runs a surplus in goods, it typically runs deficits in services and on income flows.

Much of the service deficit comes from the travel account. In the four quarters to 2024Q3, China ran a travel deficit of $200 billion or just over 1 percent of GDP. The deficit on the income account, about 0.7 percent of GDP in recent years, essentially reflects the repatriation of foreign companies’ earnings.

Between 2016 and 2023, China’s current account surplus averaged 1.4 percent of GDP. When all the data are in, I expect the current account surplus for 2024 to be around 2 percent of GDP (Figure 3).

Figure 3

In the short run, the current account reflects a country’s cyclical position. A country that is growing relatively quickly will experience a deterioration in its current account as national productive forces are insufficient to meet strong domestic demand.

Over the longer term, the current account is influenced by structural forces like a country’s propensity to save and invest. When a country runs a current account surplus, it accumulates IOUs from the rest of the world. Technically speaking, it increases its net foreign assets. Storing up IOUs that hold their value can be a good strategy. For example, it is reasonable for countries that are expected to age, or whose populations are expected to decline, to accumulate a stock of high-value IOUs. As savings rates decline, these IOUs can be used to finance consumption.

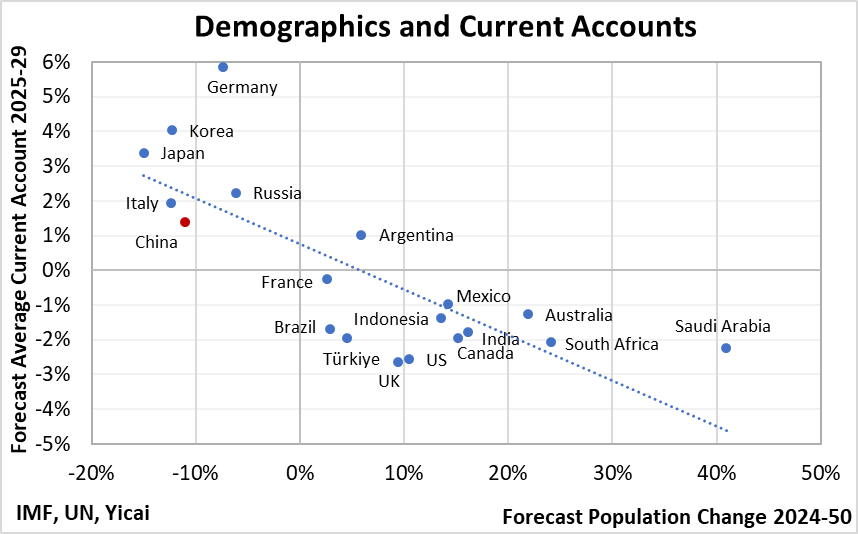

Looking across the G20 countries, we see a negative relationship between forecast current account balances and expected population growth.

Figure 4 uses the IMF’s forecast of average current account balances, as a percent of GDP, over 2025-29. This forecast looks through countries’ current cyclical positions. The current account forecasts are plotted against the UN’s projection of the countries’ population change between 2024 and 2050. Countries with populations that are expected to shrink are forecast to run current account surpluses over the next five years. In contrast, those countries whose populations are expected to grow are forecast to run deficits.

Figure 4

The IMF projects that China will run a current account surplus of 1.4 percent of GDP over the medium term, the same as its 2016-2023 average. Even a surplus of 2 percent of GDP, appears to be in line with demographic fundamentals.

With apologies to Professor Krugman, China’s trillion dollar trade surplus does not appear to be a sign of weakness. China’s surplus is large, but so is the US’s 1.2 trillion dollar deficit. China’s surplus does not seem to be the result of subsidies. Nor does it seem that China is exporting its overcapacity. China’s surplus in goods trade is partially offset by its deficits in the service and income accounts. Its projected current account surplus is not excessive and seems to be a reasonable response to coming demographic change.